Week 9: Code coverage-guided greybox fuzzing

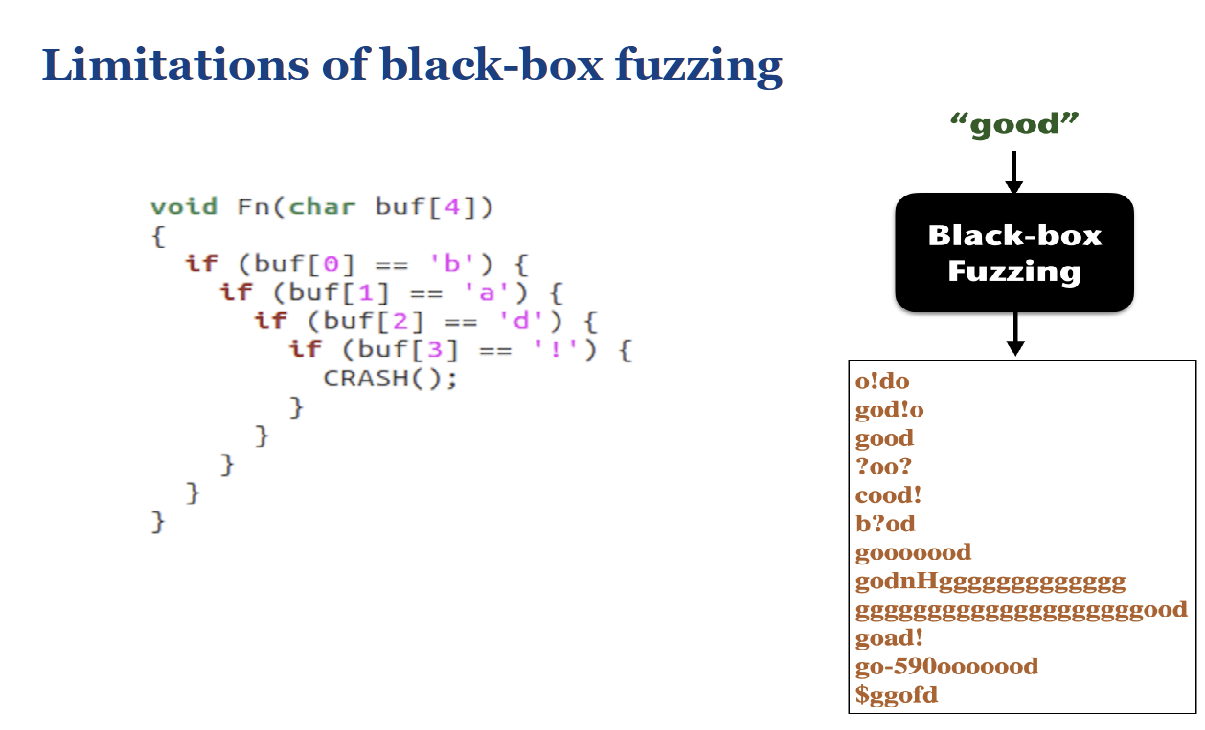

Limitations of Black-box Fuzzing

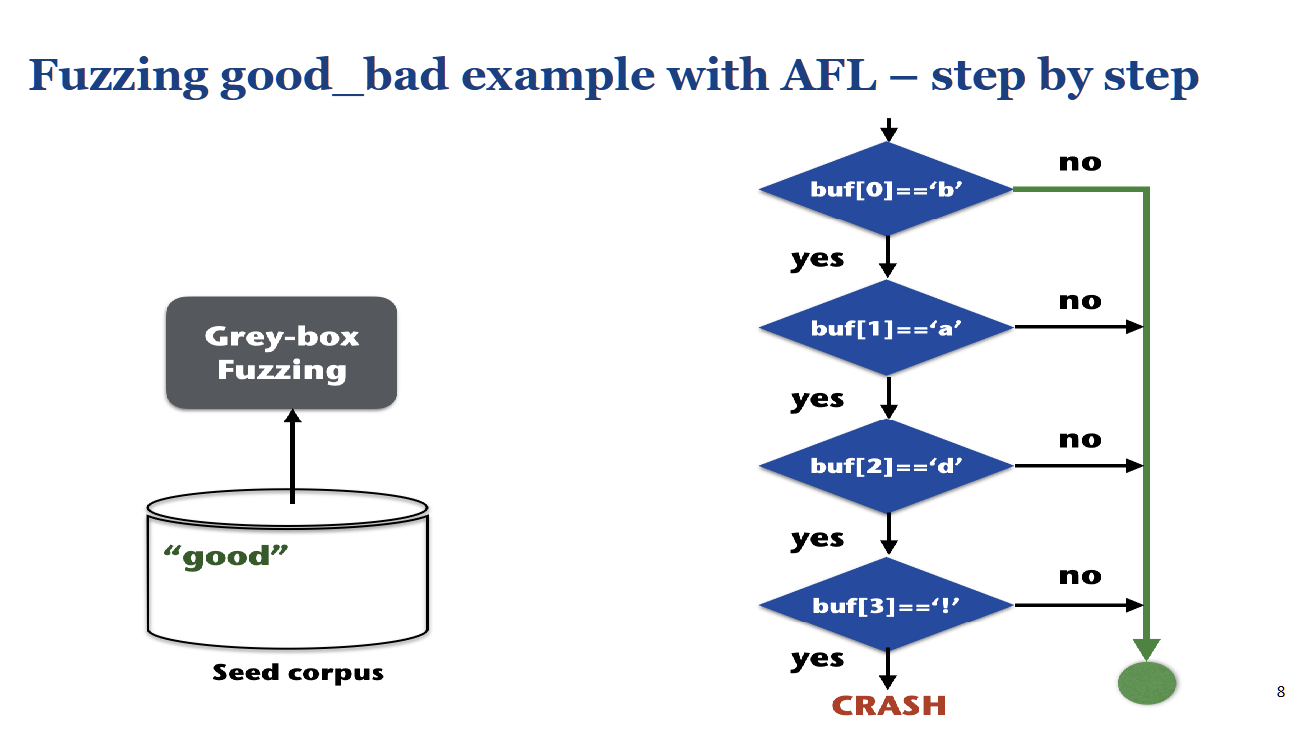

- A black-box fuzzer generates random inputs like "good", "cood!", "goad!", etc.. Since the fuzzer has no knowledge of the program's internal logic, the probability of it guessing the precise four-character sequence "bad!" is extremely low. It's effectively trying to guess a password blindfolded. 黑盒模糊器生成随机输入,如“good”、“cood!”、“goad!”等。由于模糊器不了解程序的内部逻辑,因此它猜测精确的四个字符序列“坏”的概率极低。它实际上是在试图蒙住眼睛猜测密码。

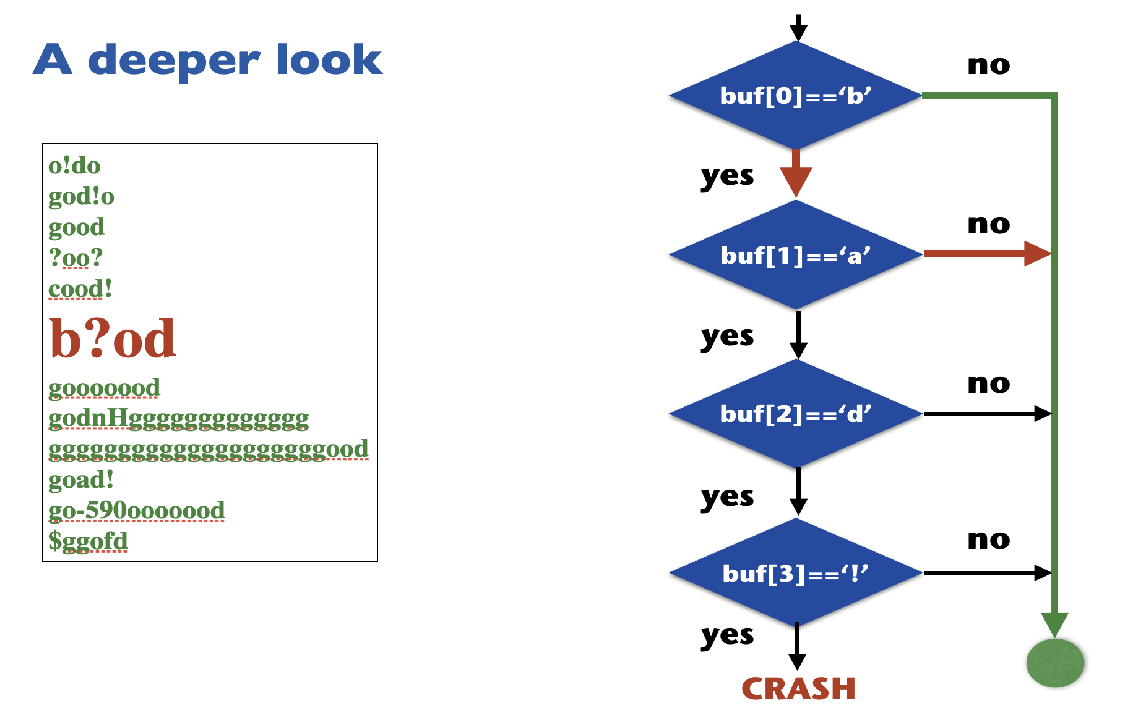

The flowchart shows that an input must pass four consecutive checks (

buf[0]=='b',buf[1]=='a', etc.) to trigger the crash.If any single check fails (the "no" path), the program exits without crashing. This clearly shows the specific, narrow path an input must follow, reinforcing why random guessing is so inefficient. 如果任何单个检查失败(“no”路径),程序将退出而不会崩溃。这清楚地显示了输入必须遵循的特定、狭窄的路径,强化了随机猜测效率低下的原因。

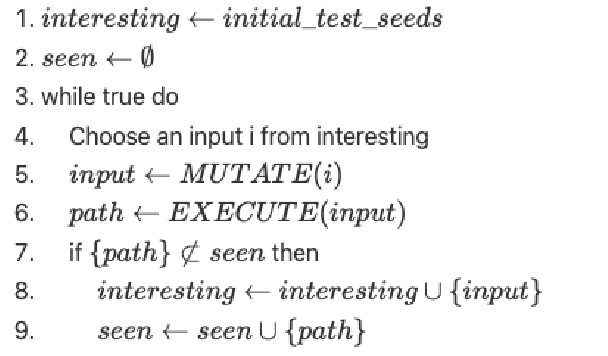

Feedback-based Greybox Fuzzing Algorithm

- Start with a queue of initial inputs, called

interestingseeds, and a set to track execution paths alreadyseen. - Enter a continuous loop.

- Pick an input from the

interestingqueue and mutate it slightly. - Execute the program with the new mutated input and record the execution path it took (this is the "feedback").

- Check the path: If this new path has never been

seenbefore, the input that discovered it is valuable. - Save the input: Add the valuable input to the

interestingqueue so it can be used as a base for future mutations, and add the new path to theseenset.

This feedback loop allows the fuzzer to learn and progressively explore deeper parts of the program, rather than guessing randomly.

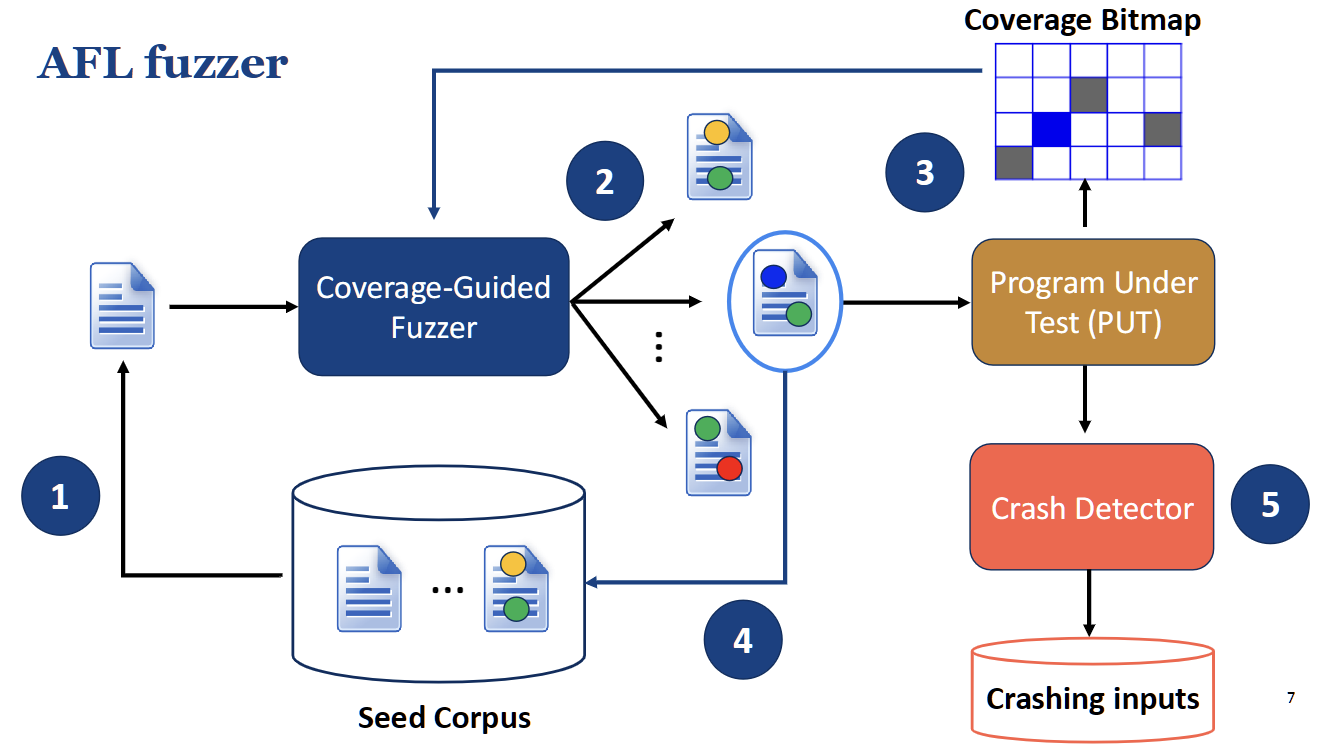

AFL Fuzzer Architecture

American Fuzzy Lop (AFL).

- Seed Corpus: The process begins with initial sample inputs (seeds). The fuzzer pulls a seed from this collection.

- Mutation: The Coverage-Guided Fuzzer engine mutates this seed to create new test cases.

- Execution & Coverage: The mutated input is fed to the Program Under Test (PUT). The program has been "instrumented" (modified) to report which code paths it executes. This information is stored in Coverage Bitmap.

- Feedback Loop: If the Coverage Bitmap shows that the new input executed a new path, the input is considered "interesting" and is added back to the Seed Corpus to be used for future mutations.

- Crash Detection: If the program crashes, the fuzzer saves the input that caused it for later analysis.

Fuzzing the "bad!" Example with AFL

- Start: The fuzzer starts with an initial seed, like "good".

- First Discovery: It mutates "good" and eventually generates an input like "bood". It runs "bood" and sees from the coverage feedback that it passed the first check (

buf[0]=='b')—a new path! - Save & Prioritize: The fuzzer adds "bood" to the seed corpus because it's interesting.

- Incremental Progress: It now focuses on mutating "bood". It eventually generates "baod", which passes the first two checks—another new path. "baod" is also saved.

- Solve: This process continues, with the fuzzer incrementally solving each condition until it generates "bad!" and triggers the

CRASH.

Discussion on Feedback Signals

- Is code coverage the best feedback? It prompts a discussion on whether other metrics could guide a fuzzer more effectively.

- How to fuzz binaries? It asks how to get code coverage feedback when you don't have the source code. This involves techniques like QEMU or dynamic binary instrumentation.

- How to fuzz remote services? It raises the challenge of fuzzing programs you can't directly execute, like a web server, where you can't get code coverage easily.